The Bubble Burst: What’s Next For LeBron James And The NBA After Historic Ratings Collapse?

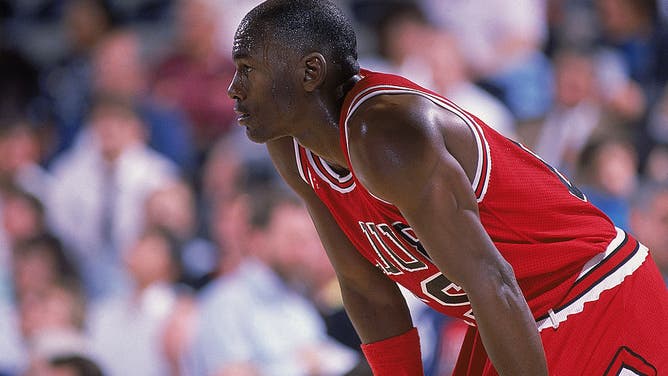

LeBron James is supposed to be must-see TV. His whole career has been billed as the next Michael Jordan, Muhammad Ali and Tiger Woods all rolled into one.

He relocated to Hollywood not just to be the biggest attraction in sports, but also to rival the star power of DiCaprio, Denzel, Damon and Depp.

So why didn’t anyone watch James’ latest blockbuster?

On Sunday, he inched closer to Jordan, winning his fourth NBA title and fourth NBA Finals MVP. He did it while wearing the glitziest, star-making uniform in sports, a Los Angeles Lakers jersey.

But when the Lakers beat the Miami Heat in Game 6 to win the title Sunday night, just 5.6 million people watched, according to Nielsen Media Research. That’s less than one-third of the people who watched Game 6 last year between Golden State and Toronto.

In 1998, when Jordan won the title in a Game 6 on a Sunday night, 36 million people watched. In fact, the average episode of “The Last Dance,’’ the 10-episode ESPN documentary on Jordan’s final title run, averaged the same number of live viewers as the Lakers’ deciding game against the Heat. The Lakers-Heat series finished as the least-watched NBA Finals of the last 40 years.

What just happened? And why?

Is the COVID-19 pandemic a basketball-market circuit breaker, a temporary halt to the game’s popularity? Or has the league’s embrace of politics and protest caused a market collapse?

You have to ask all these questions now. Surely ABC/ESPN and TNT are asking. They have the NBA rights locked up through 2025 in a contract that requires them to pay $2.2 billion per year.

Maybe playing a season in a bubble was a big mistake. Maybe the social justice messaging was overdone. Go woke, go broke? What does the league have to do to recover?

“How long do you have?’’ Peter Vecsey, longtime New York sports columnist and analyst on TBS and NBC, told OutKick. “What do they have to do? Like, everything. . .and then bring back Jordan. Look, the NBA has turned me off completely. And with the politics brought into it, they’ve already lost half the fans.’’

“In a normal world,’’ NBA legend Isiah Thomas told OutKick, “we could achieve and strive for things. Once COVID hit, it’s all survival mode. To try to hold leagues to an unrealistic standard of normalcy -- I don’t think that’s fair.’’

“It doesn’t matter where you fall on the political spectrum,’’ legendary sports broadcaster Bob Costas told OutKick, “it’s just a fact that there is alienation over having this (social justice messaging) thrust in everyone’s face every time you just want to watch a game. I’m not saying that to take a stand; that’s just the reality. This is also a business.’’

“The NBA is going through a perfect storm,’’ former NBA coach Doug Collins, who was one of Michael Jordan’s coaches with the Bulls, explained to OutKick. “Everything came together at the same time. COVID, the economic crisis, social injustices. People’s lives have been turned upside down.’’

From across the sports landscape, different experts gave OutKick different explanations about what’s at stake for LeBron and the NBA. I talked with legendary former players and coaches, sports business experts and media analysts. To me, there is one undeniable fact:

When Jordan played, people had to watch. When Ali fought, people watched. If Tiger Woods is in the lead in the final round of the Masters in mid-November, people will stop what they’re doing to watch. That’s the power of the pursuit of history, athletic brilliance and charisma. It won’t matter that the Masters is normally played in April.

The all-time, all-time greats are always must-see TV.

The entire point of the NBA bubble was the preservation of 35-year-old LeBron and the Lakers’ title quest. LeBron and the Lakers, two iconic brands, were supposed to be immune from the harshest ravages of the COVID-19 pandemic.

So why did the bubble burst?

Black Lives Matter and the Anthem

Black Lives Matter changed the entertainment equation for sports. Games that traditionally started with the National Anthem, wrapped in a pristine, easily digestible and celebratory view of Americana, have become full-blown expressions of what’s wrong with the USA.

Whether the players are right or wrong doesn’t matter. It’s disconcerting to a large portion of the audience. It was counter-marketing to the image of an NBA bubble at Disney World, the Happiest Place on Earth.

Imagine Disney pivoting away from Mickey Mouse and making Cardi B its pitchman. Imagine women dressed in Hooters attire strapping seat belts on mom, dad and their pre-teen kids as they board Space Mountain. It’s not the worst idea, but no one would express surprise if a portion of the traditional customer base complained loudly and ended their patronage.

B.J. Armstrong understands the business of basketball. A 53-year-old former teammate of Jordan, front-office executive for the Chicago Bulls and current player agent, he has been around the game for decades.

Armstrong believes that when it comes to social justice messaging, you cannot separate the business aspects of basketball from the players’ humanity.

“I go back to who I am,’’ he said. “For 53 years, I’ve been a black male in America. I can’t tone down that I’m a black American. I can’t tone that down.’’

You didn’t have to look far to see social justice messaging in the NBA bubble. It was painted right on the court: Black Lives Matter. Other messages were on the backs of jerseys and patches on coaches’ shirts.

It was the theme of the basketball season, with players gaining control of their sport and wanting to take a stance on the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor. The Milwaukee Bucks refused to play after a policeman shot a Wisconsin man, Jacob Blake, seven times in the back. The Bucks’ refusal shut down the bubble.

Was it too much?

“It’s too early to say that. There are conflicting constituencies on this,’’ said Marc Ganis, president of Sportscorp Ltd., a leading sports consulting firm.

If you want to build a stadium, sell your team, or make broadcast deals, you call Ganis. He is a regular adviser to NFL owners. Ganis also has advised Major League Baseball owners on media rights.

“There are fans that don’t want politics forced down their throats during sports events,” he continued. “And there are players who want to use their platform to get their interests across. And there are NBA owners, who have it in their DNA to push social justice messages. How do you satisfy all of them without getting players upset, players being heard and respected, owners’ DNA being satisfied and fans not feeling overwhelmed?’’

Ganis said that if any league becomes “excessively political,’’ it will lose some fans who use sports to get away from life’s realities.

But 2020 is an aberration, Ganis said. Give everything that happens this year a mulligan. There are too many potential other factors for fading interest in the NBA to pin the ratings on social justice messaging.

His point -- and several other experts made the same one -- is that it’s not comparing apples to apples when you compare this year’s NBA ratings to any other year.

We’ll get a more accurate look at the NBA’s health next season, assuming things are more back to normal. And Ganis believes that if the social messaging continues this strong next year, it could be a problem for the NBA. Fans might be more accepting of it this year — a year of national angst — than in the future.

Costas, looking purely from the business perspective, saw other potential issues. He said there is a long history of athletes using their platform to address social issues.

Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised a gloved fist at the 1968 Olympics. But that was a one-time thing, Costas said. He pointed out that Ali’s messages were “effective and significant.’’

“But another question I think is relevant is this: If you’re going to permit social justice messages -- which I am not opposed to -- let’s look at this with a clear eye (and not say) which of these messages we agree and disagree with.’’

Costas asked how the NBA can stop a player who wants to push the message “Free Hong Kong,’’ which hits closely to the NBA’s financial ties to China. Or what if a player wants a pro-Trump message?

So what can the NBA do from here? Does it need an exit strategy from social messaging?

“Players can find different parts of their platform to use, their own press conferences, Twitter accounts, sponsorship deals,’’ Ganis said. “Does it have to be in the three-hour window (during games)?’’

He said owners can fund the players’ social justice efforts, too. That way, players, owners and fans can all be satisfied.

“I can’t put my finger on why some people get turned off because of social issues that people take a stand on, which I applaud,’’ said Jim Jackson, a former NBA player and current TNT broadcaster. “You can’t take the voice away from the players.’’

But can you take it away from the games and put it on a billboard?

“Not possible,’’ Armstrong said. “After playing professional basketball, being an athlete and all those things, this all comes down to one thing for me: respect.

“People see me and say, `You played for the Bulls. But how many people actually see me? Do you see your jersey, favorite team, favorite athlete that plays for the team. Or do you see. . .me?

“So now what you’re doing is asking me to not be authentically myself. My question is `Do you not want to deal with it, or not want to see me?’ I respect you; you respect me. From that respect, you and I can now have an intelligent conversation about how to solve this perceived problem.’’

Expansion and ambition

Nearly two decades ago, the National Basketball Association and its shoe partner, Nike, launched the product intended to replace Michael Jordan as the game’s greatest ambassador -- LeBron James.

On its then-all-powerful cover, Sports Illustrated hailed the 17-year-old as “The Chosen One,” the heir to Air Jordan. The first name mentioned in the profile story of the would-be King was Michael Jordan, not LeBron James.

The rollout of the NBA and Nike’s marketing campaign instantly established the stakes: King James would chase the ghost of Michael Jordan.

As campaigns often do, the LeBron crusade reacted to societal changes and expanded its ambition. While James was winning titles as a member of the Miami Heat, a black teenager, Trayvon Martin, was killed by a volunteer neighborhood watchman in Florida, sparking the Black Lives Matter movement.

The LeBron crusade recalibrated, diving headfirst into social activism surrounding police brutality and eventually politics. James campaigned for Hillary Clinton in 2016. He financed a significant portion of a school in his hometown of Akron. He publicly sparred with President Trump. He’s now the face of a voter drive.

LeBron James chased Muhammad Ali, the most internationally relevant sports figure in American history, an athlete known for his importance inside and outside the arena of sports.

LeBron took on all comers. Tiger Woods and Babe Ruth, Wayne Gretzky and, yes, Jordan and Ali, too. Every time he stepped onto the court, we were watching history. It was perfect.

The problem is, James isn’t Ali. He isn’t Jordan. Woods. Gretzky. Any of these guys. For one thing, he isn’t the greatest player of all time. That’s a campaign that ESPN, TNT, and Nike are pushing. It’s a campaign that works for the talk shows built around endless arguments.

ESPN’s “Last Dance’’ ruined the Jordan-vs-LeBron narrative. The NBA’s television partners do what they can to convince us that what we’re seeing now is better than anything we’ve seen before. It’s a clever gimmick perfect for an American public trained to document their witnessing of and participation in history on Facebook and Instagram.

“Last Dance’’ disrupted the illusion, reminding us of the reality of Jordan’s historical greatness, competitiveness and ability to captivate. No one honestly believes anymore that James can catch Jordan.

James plays in the wrong television era to compete with Jordan and the other all-time greats. Jordan didn’t surpass Bill Russell, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Magic Johnson and Larry Bird because studio debate shows said so. Jordan slayed the NBA dragons with sustained on-court brilliance so awe-inspiring that his ascendance to the throne was never even debated.

It was a story of history being told, and you had to watch every minute.

“Back in the day, you wanted to watch Michael Jordan or Magic and it was something amazing. You had to invest that 2½ hours, then watch maybe later on SportsCenter,’’ said Andrew Marchand, the sports media reporter for the New York Post. “You had to make an appointment to be there.

“Younger demographics don’t even think about turning on TV. Do they put on cable TV or broadcast networks? I don’t know any kid that does that. There isn’t any reason to be on Turner (watching) unless you’re a fan of the NBA … The NBA is losing (the) drive-by audience.’’

Of course, customers consumed sports media differently in Jordan’s day. Now, Marchand said, if you don’t turn on the TV, LeBron’s highlights will pop up on social media in a few minutes.

“That can’t-miss moment?’’ Marchand said. “You can miss it now.’’

The lack of conflict, rivalry and animus have made basketball far less compelling drama than the NFL. The NBA has become a highlight show. Jordan, Bird, Magic were so compelling you didn’t want to reduce them to highlights.

You don’t condense Tiger Woods into highlights. Or Tom Brady.

But that’s exactly what James is, a series of highlights, not a real narrative that people believe.

Armstrong said he took his kids to an NBA Finals game two years ago, Golden State against Cleveland, and they were sitting up close, in the sixth or seventh row.

“We’re at the game,’’ Armstrong said. “We’re AT the game. And my son says, `Hey dad, check this out.’ He shows me the game on his phone.

“I said, `I know, we just saw that play live. We could almost have touched the players.’ “

So James is at the stadium and on your TV, but he’s also in your pocket, on your phone or wherever you go.

And maybe that’s too much James. Is there such a thing as LeBron Fatigue?

“We didn’t get Michael Jordan Fatigue,’’ Jackson said. “But we didn’t have social media then, either. LeBron has benefitted from it, but is hurt a little bit by it, too.’’

Fans are forgiving, to a point

In 1994, Major League Baseball got into labor battles -- millionaire players vs. billionaire owners -- and it spilled into the fans’ entertainment and spoiled their fun.

They canceled the World Series.

When baseball came back, fans were not automatically forgiving. Attendance fell, and players suddenly were taking the field before games and staying after them to sign autographs.

Costas said the NBA can learn from MLB how to reconnect and recover from the bubble season.

“A lot of fans were alienated by the constant squabble over finances,’’ he said. “Here’s what happened: They came back and they played, and slowly fans came back.”

Costas pointed to the night in 1995 when Cal Ripken passed Lou Gehrig’s record for consecutive games played. And then, of course, there was the 1998 home run chase between Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa.

“A lot of things that put the focus back on the game happened,” Costas said. “So maybe that’s the short answer: When the focus was put back on the game, the game’s appeal asserted itself.’’

Collins and Vecsey say that if the game is to sell itself, though, it could use a little tweaking.

“The beauty of the game is there,’’ Collins said. “The players today are so talented.’’

But Collins, an analytics guy, is worried. He said that statistics show that a 12- or 15-foot jump shot for two points isn’t worth the risk anymore. So offenses run down the floor and plant two players in the corners beyond the 3-point line. Then, two defenders stand next to them and the mid-court game is no longer in existence.

“We’ve taken away the part of the floor where Hall of Famers used to hang out,’’ Collins said. “Most every team plays the same way now.’’

And Collins believes the fraternization among players and lack of intense rivalries is also hurting the game.

“In watching ‘The Last Dance,’ I had a lot of people come up to me and said it took them back to a style of play that is no longer around, of teams not liking each other,’’ he said. “All these players you see today have grown up through AAU basketball. They know each other. They’re friends.’’

To me, the game today looks like the All-Star Games of the past, an exhibition where players just spread out and don’t do the dirty work close to the basket. In Jordan’s days, the Detroit Pistons had Jordan Rules, where someone was supposed to knock him to the court as hard as possible every time he got near the basket.

Not everyone thinks the NBA has a problem. John Ourand, who covers the media for Sports Business Journal, said he is “bullish on the NBA as a TV property.’’

“Yes, this is going to be the lowest NBA Finals series on record, but it’s a bad comparison,’’ he said. “The NBA Finals have never gone up against the NFL. It had to go against the baseball playoffs, the NHL Stanley Cup, college football starting up.

“The NBA is down, of course. The NFL is down. MLB is down. NHL, college football, horse racing, NASCAR. In all those sports, you’re seeing ratings drop, but in aggregate, the amount of sports viewing has actually increased.’’

Ourand acknowledged that NFL ratings are down just 10 percent, which is nowhere near the record crash of NBA ratings.

Still, Ourand believes TNT and ESPN are not nervous about their investments.

There are always multiple reasons for ratings drops. For one, cord-cutting has affected the NBA more than other sports, he said, because younger people who don’t watch TV on cable make up a good chunk of the NBA audience.

He and Armstrong both said that the NBA is well-aware that its future is in getting to consumers on their phones.

But how do you monetize that?

“Everybody’s trying to figure that out,’’ Ourand said.

Thomas is even more positive about the NBA than Ourand. In fact, he thinks the NBA season was a smashing success, playing at an unfamiliar spot on the calendar.

“The bubble worked in terms of completing the season,’’ he said. “If you get into survival mode in terms of completing the season, the NBA players, sponsors and businesses all did what we had to do.

“I don’t think you measure anything as good or bad during COVID. You have to measure it by `Did you survive?’ You’ve got to remember where it all started. We all started from zero with a blank piece of paper. This has never been done before in a pandemic.’’

So imagine next season. The NBA is in its regular time slot. And James is back again, going for yet another championship.

Will you be watching?

“I’ve turned off the league,’’ said Vecsey, who did not watch one postseason game this year. “Do they honestly believe they’re going to get people back when it’s time to sell tickets?’’

You can dismiss Vecsey as an old man longing for days gone by. What you can’t do is argue the NBA is replacing season-ticket holders and television viewers who share his perspective with a new crop of basketball addicts.