Americans Overwhelmingly Think Social Media Negatively Affects the Country

Social media platforms Twitter and Facebook are in the crosshairs this week after censoring the New York Post bombshell about alleged emails and texts pulled from Hunter Biden's laptop.

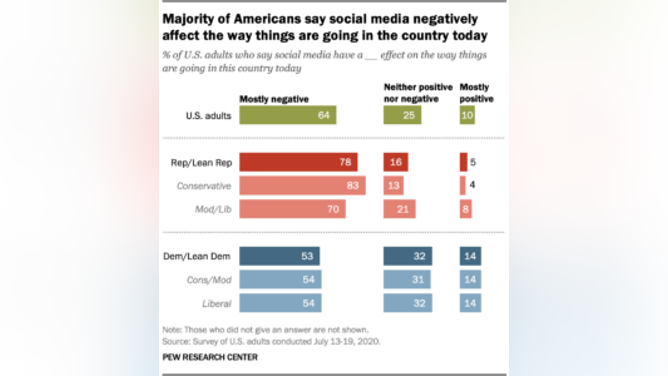

However, Americans have been expressing discomfort with the rising role of social media in daily life for a while now. In mid-July, Pew Research released a survey showing that 64 percent of U.S. adults believe that social media negatively affects the way things are going in the country. Just 10 percent believe its impact is "mostly positive":

At this moment, negative perceptions of social media are more concentrated among Republicans than Democrats. In May and June, right before this survey was taken, Twitter repeatedly attached warning labels to President Trump's tweets. And though Republicans have held the presidency and Senate for the past four years, they have not levied meaningful constraints on Big Tech.

However, this is still a bipartisan issue. Only one out of four Democrats expressed a positive view of the impact of social media, though the reason behind this negative viewpoint might be vastly different than for Republicans. Some Democrats still hold Twitter and Facebook responsible for amplifying then-FBI Director Jim Comey's further investigation into Hillary Clinton's emails in October 2016, and these platforms do not want to be accused of swinging the election for Trump again.

Nonetheless, they have learned that the best way to maximize the market share of our attention is to keep us agitated. Users take extreme positions in order to earn more likes and retweets, which then encourage more division and tribalism. Moderation doesn't attract much attention.

The pandemic has kept us all cooped up in our homes much more than normal. Even though the social platforms have probably done more harm than good for years, we are more acutely aware of them now.

But there's a wild difference between social media and real life. You see it all the time. Imagine yourself right now throwing a picnic in a park on a nice day. Everyone there is in a good mood. Are these same people spreading good vibes into the air also slinging mud at others online? It's difficult to imagine that they are.

The weird thing is that all of us who are Very Online know that social media has ravaged our brains. There have been stories documenting it for years. "The Social Dilemma" on Netflix has raised awareness most recently. And yet we don't log off.

Twitter went down for about an hour last night. It was blissful. Le'Veon Bell signed with the Chiefs during this time, and no one knew. The world kept on spinning. We should all untether ourselves from social media platforms as well as our phones.

There's also the question about whether elected leaders ought to regulate these platforms. Even if they should, they don't seem to care. Neither the Republicans nor Democrats have taken the initiative to pass meaningful legislation against Big Tech.

The writer Matthew Stoller made the case in a New York Times op/ed last year that Google and Facebook were siphoning off the money from journalism and had too much control over the flow of information. He concluded that they should be broken up:

"To save democracy and the free press, we must eliminate Google and Facebook’s control over the information commons. That means decentralizing these markets and splitting information utilities from one another so that search, mapping, YouTube and other Google subsidiaries are separate companies, and Instagram, WhatsApp and Facebook once again compete. It also means barring or severely curtailing advertising on any of these platforms. Advertising revenue should once again flow to journalism and art. And people should pay directly for communications services, instead of paying indirectly by forgoing democracy."

Breaking them up may leave individual components susceptible to crushing competition from tech firms in China and elsewhere, but Big Tech has a problem even if they stay together. The American people have applied steady pressure on Congress to address the problem of social media, and even Congress can't ignore their constituents forever.

In the meantime, we should all try to be conscious of how much time we are giving these platforms and commit ourselves to taking some of it back.